Cutaneous T Cell

Lymphoma

Introduction

Lymphoma is a type of cancer that begins in a

lymphocyte. This disease is divided into two major categories: Hodgkin lymphoma

and all other lymphomas (also referred to as non-Hodgkin lymphomas).

A lymphocyte is a type of white cell. Lymphocytes

compose about 20 percent of the white cells in the blood. Most lymphocytes are

found in the lymphatic system, the major part of the body's immune system. The

lymphatic system consists of a network of organs, including the spleen, the

lymph nodes (small bean-shaped structures located throughout the body), the

lymphatic vessels and areas in the gastrointestinal tract.

The three main types of lymphocytes are: T

lymphocytes, B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. These cells circulate

throughout the body within the lymphatic vessels, suspended in a watery fluid

called lymph. The lymphatic vessels ultimately empty into the bloodstream.

Using the network of lymphatic vessels, lymphocytes are transported to

locations around the body where they are needed to

respond to infectious organisms, especially bacteria, fungi or viruses. On

contact with these infectious agents, T and B lymphocytes work in coordination

to make antibodies. The antibodies coat the infectious agents, making them

susceptible to ingestion and destruction by other white cells (called

neutrophils and monocytes). Also, NK cells can attack

virus-infected cells and help to resolve viral infections.

Most lymphomas begin in a lymphocyte in a lymph node,

when damage to cell DNA causes a cell change (mutation). The now abnormal cell

divides, and subsequent cells grow in an uncontrolled way, forming a tumor. Additional

tumors may grow in other lymph nodes or in tissues such as liver, lung and

bone. Some lymphomas begin in other lymphatic structures or in organs, such as

lymphoma of the stomach.

Cutaneous or skin lymphoma begins in a lymphocyte in

the skin. Because the medical term for the skin is the cutaneous tissue

or system, “cutaneous lymphoma” is the formal name for lymphoma of the skin.

This disease may also be called “skin lymphoma.” The term “cutaneous lymphoma”

or “skin lymphoma” actually describes a number of different disorders with

various signs and symptoms, outcomes and treatment considerations. Most skin

lymphoma begins in a T lymphocyte that has undergone a malignant change. This

disease is called “cutaneous T-cell lymphoma” or CTCL. Older descriptive terms,

such as “mycosis fungoides” and “Sézary syndrome,” are types of cutaneous

lymphomas that are now also referred to as CTCL.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of

CTCL. As a result, more is known

about it than other types of skin lymphomas. The name

comes from the mushroom-like skin tumors noted in the first patient diagnosed.

MF is usually a low-grade (slow-growing or indolent) lymphoma that primarily

affects the skin. It often remains confined to the skin. In general the

prognosis for MF is considered to be good. Most patients are diagnosed in early

stages with skin involvement only, and the disease does not progress to the

lymph nodes or internal organs. However, in a minority of cases MF does slowly

progress. Sézary syndrome is a related, but more aggressive form of CTCL, with

widespread skin effects and the presence of malignant lymphocytes in the blood.

This condition is characterized by an extensive red rash and sometimes loss

(sloughing) of the exterior layers of the skin. It was identified by the French

dermatologist Sézary, who first reported that some people with this skin

condition also had malignant lymphocytes in the blood.1

The overall annual incidence of primary CTCL in the US in 1988 was 0·5–1·0 per 100 000 based on population data. However, the prevalence is much higher because most patients have low-grade disease and live long. Males and the black population are affected more commonly.2,3 The incidence has increased during the past two decades but this almost certainly reflects improved diagnosis of earlier stages and possibly better registration, particularly in the US.2

Aetiology

The underlying aetiology is unknown. There is evidence for inactivation of key tumour suppressor genes and TH2 cytokine production by tumour cells in mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome, but no disease-specific molecular abnormality has yet been identified. Primary CTCL must be distinguished from human T-lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-I) associated adult T-cell leukaemia lymphoma (ATLL) in which skin involvement often closely mimics the clinicopathological features of mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome and may be the presenting feature.2

Mycosis Fungoides

Mycosis fungoides represents the most common type of

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It is also a long-standing entity, having been

described almost two centuries ago, in 1806, by the French dermatologist

Alibert. Traditionally, it is divided into three clinical phases: patch, plaque

and tumour stages. The clinical course can be protracted over years or decades.

The term ‘mycosis fungoides’ should be restricted to the classic so-called

‘Alibert–Bazin’ type of the disease, characterized by the typical slow

evolution and protracted course. More

aggressive entities (e.g. mycosis fungoides ‘a tumeur d’emblee’), characterized

by an onset with plaques and tumours, an aggressive course and a bad prognosis,

are better classified among the recently described group of cutaneous cytotoxic

T- (NK/T-) cell lymphomas.

In the past, mycosis fungoides has been considered as

an ‘incurable’, albeit slowly progressive disease, that inevitably ended with

the death of the patient. Recently, an early

form of mycosis fungoides has been recognized,

consisting of subtle patches of the disease. These patients have relatively

mild stable disease, which questions the traditional

concept of the inevitability of disease progression

until death. The aetiology of mycosis fungoides remains unknown. A genetic

predisposition may have a role in some cases, and a familial occurrence of the

disease has been reported in a few instances. Association with long-term

exposure to various allergens has also been advocated, as well as exposure to

environmental agents and association with chronic skin disorders and viral

infections. Recently, seropositivity for cytomegalovirus (CMV) has been

observed at unusually high frequencies in patients with mycosis fungoides,

suggesting a role for this virus in the pathogenesis of the disease. In some

countries, mycosis fungoides-like disorders are clearly associated with viral

infections (human T-cell lymphotrophic virus I [HTLV-I]-associated adult T-cell

lymphoma–leukaemia), but the search for viral particles in patients with

mycosis fungoides has so far been unsuccessful. Genetic alterations have been

identified mainly in late stages of the disease, and their importance for

disease initiation is unclear.

Mycosis fungoides has been

described in patients with other haematological disorders, especially

lymphomatoid papulosis and Hodgkin lymphoma. In occasional patients, the same

clone has been detected in mycosis fungoides and associated lymphomas, raising

questions about a common origin of the diseases. In addition, patients with

mycosis fungoides are at higher risk of developing a second (non-haematological)

malignancy.

A staging classification

system for mycosis fungoides was proposed in 1979 by the Mycosis Fungoides

Cooperative Group (TNMB staging). This system takes into account the percentage

of body area covered by lesions, and the presence of lymph node or visceral

involvement. Although the presence of malignant circulating cells in the blood

should be recorded for each patient, these data are not used for staging. More

recently, a new staging classification for mycosis fungoides has been proposed

in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of haematopoietic

neoplasms. Some centres specializing in the study and management of skin

lymphomas do not utilize the TNM or WHO staging schemes, but classify mycosis

fungoides according to the type of skin lesions (patches, plaques and tumours)

and the presence or absence of large cell transformation and/or extracutaneous involvement.

In this classify, stage I disease is confined to the skin and characterized

morphologically by patches only. Survival is extremely long in these patients

(usually decades), and nonaggressive treatments should be applied. Most

patients in this stage die of unrelated causes. Patients with stage II in this classify

also have disease limited to the skin, but characterized morphologically by the

presence of plaques, tumours or erythroderma, or by large cell transformation

histopathologically. The disease in these patients is inevitably progressive, and

treatment should be more aggressive. Stage III patients have extracutaneous

disease and should be managed with aggressive treatment options. Staging

investigations are not necessary in early stage mycosis fungoides (patch

stage). Patients with plaques, tumours or erythroderma should be screened for

extracutaneous involvement (laboratory investigations, sonography of

lymphnodes, computerized tomography (CT) scan of thorax and abdomen, bone

marrow biopsy, examination of the peripheral blood). Although the presence of a

monoclonal population of T lymphocytes within the peripheral blood has been

observed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique in some patients with early mycosis fungoides, in

many of these cases the clone was different

from that detected in the skin lesions. In addition, the prognostic value of

the detection of monoclonality in the peripheral blood is unclear. It has been

suggested that flow cytometry analysis is highly effective in demonstrating and

quantifying small numbers of circulating tumour cells in patients with mycosis

fungoides.4

Lesions of mycosis fungoides can be divided

morphologically into patches, plaques and tumours. Itching is often a prominent

symptom. Erythroderma may develop in the course of the disease, rendering

distinction from Sézary syndrome difficult without a proper clinical history.4,5,6,7

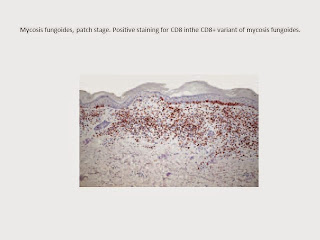

Patch stage

Patches of mycosis fungoides are characterized by

variably large, erythematous, finely scaling lesions with a predilection for

the buttocks and other sun-protected areas . Loss of elastic fibres and atrophy

of the epidermis may confer on the lesions a typical wrinkled appearance, and

terms such as ‘parchment-like’ or ‘cigarette paper-like’ have been used to describe them. Sometimes, these single patches

have a yellowish hue, conferring a ‘xanthomatous’-like aspect to the lesions

(xanthoerythroderma perstans). In early phases, a ‘digitate’ pattern can be

observed (alone or in combination with larger patches; see also smallplaque

parapsoriasis).4,7,8

Plaque stage

Plaques of mycosis fungoides are characterized by

infiltrated, scaling, reddish brown lesions. Typical patches are usually

observed contiguous to plaques or at other sites on the body. Plaques of

mycosis fungoides should be distinguished from flat tumours of the disease. Flat

infiltrated lesions should be biopsied in order to allow histopathological

examination and a precise classification of the lesions.4,7,8

Tumour stage

In tumour-stage mycosis fungoides a combination of

patches, plaques and tumours is usually found, but tumours may also be observed

in the absence of other lesions. Tumours may be solitary or, more often,

localized or generalized. Ulceration is common. In tumour-stage mycosis

fungoides unusual sites of involvement may be observed, such as the mucosal

regions. As oral and genital mucosae are frequently involved in cytotoxic

T/NK-cell lymphomas, care should be taken to classify these cases correctly.

Careful clinical history taking, re-evaluation of previous biopsies, and

complete phenotypical and genotypical investigations are mandatory to make the

diagnosis of mucosal involvement in mycosis fungoides.4,7,8

Histopathology

Early lesions of mycosis fungoides reveal a patchy

lichenoid or band-like infiltrate in an expanded papillary dermis. A

psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis may be seen , but in most cases the

epidermis is normal. Small lymphocytes predominate, and atypical cells

can be observed only in a minority of cases.

Epidermotropism of solitary lymphocytes is usually found, but Darier’s nests

(Pautrier’s microabscesses) are rare. Useful diagnostic clues are the presence

of epidermotropic lymphocytes with nuclei slightly larger than those of

lymphocytes within the upper dermis and/or the presence of lymphocytes aligned along the basal layer of the

epidermis. Also useful is the presence of many intraepidermal lymphocytes in

areas with scant spongiosis. In this context, it should be emphasized that in a

few cases (approximately 5% of the total) epidermotropism may be missing. The

papillary dermis shows a moderate to marked fibrosis with coarse bundles of

collagen and a band-like or patchy lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes. Dermal

oedema is usually not found. Unusual histopathological patterns of mycosis

fungoides in early phases include the presence of a perivascular (as opposed to

band-like) superficial infiltrate, prominent spongiosis simulating the picture

of acute contact dermatitis, an interface dermatitis, sometimes with several necrotic

keratinocytes, marked pigment incontinence with melanophages in the papillary

dermis, prominent epidermal hyperplasia simulating the picture of lichen

simplex chronicus and prominent extravasation of erythrocytes. A pattern characterized

by a markedly flattened epidermis, a lichenoid infiltrate in the dermis and

increased dilated vessels in the papillary dermis is the histopathological

counterpart of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Cytomorphologically, small

pleomorphic (cerebriform) cells predominate. In some cases, plaques or flat

tumours of mycosis fungoides may present with a predominantly interstitial

infiltrate. This peculiar presentation can give rise to diagnostic problems,

and has been designated ‘interstitial mycosis fungoides’. Immunohistology

confirms that interstitial cells are T lymphocytes, thus being a helpful clue

for the differential diagnosis with the interstitial variant of granuloma

annulare. Intersitial mycosis fungoides is usually a manifestation of either

the plaque or tumour stage of the disease. In tumours of mycosis fungoides, a

dense nodular or diffuse infiltrate is found within the entire dermis, usually

involving the subcutaneous fat. Epidermotropism may be lost. Flat tumours are

characterized histopathologically by dense infiltrates confined to the

superficial and mid parts of the dermis. Angiocentricity and/or

angiodestruction can be observed in some cases. A peculiar histopathological

presentation of mycosis fungoides characterized by marked involvement of

hyperplastic sweat glands has been termed ‘syringotropic’ mycosis fungoides. In

some of these cases, syringometaplasia can be observed. Involvement of the

epidermis may be missing in syringotropic mycosis fungoides, thus creating

problems in the histopathological diagnosis of this variant of the disease.4,6,7

Immunophenotype

Mycosis fungoides is characterized by an infiltrate

of α/β T helper memory lymphocytes (βF1+, CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD8–, CD45RO+).

Only a minority of cases exhibit a T-cytotoxic (βF1+, CD3+, CD4–, CD5+, CD8+)

or γ/δ (βF1–, CD3+, CD4–, CD5+, CD8+) lineage that show no clinical and/or

prognostic differences. In these cases, correlation with the clinical features

is crucial, in order to rule out skin involvement by aggressive cytotoxic

lymphomas such as CD8+ epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma or γ/δ T-cell lymphoma.

In late stages there may be a (partial) loss of pan-T-cell antigen expression.

In

plaque and tumour lesions, neoplastic T cells may

express the CD30 antigen. Recently, it has been suggested that a low CD8 : CD3

ratio in skin infiltrates supports the histopathological diagnosis of mycosis

fungoides, but this finding should be confirmed by larger studies.

Cytotoxic-associated markers such as TIA-1 and granzyme B are negative in

mycosis fungoides, although occasionally in late stages of the disease some

positivity may be observed. These cases should not be classified as cytotoxic

lymphomas, but as tumour-stage mycosis fungoides with cytotoxic phenotypes. A

similar phenotype may also be seen in early lesions of the rare γ/δ+ mycosis

fungoides, which besides cytotoxic proteins also express CD56.4

Histopathological Differential Diagnosis

The histopathological diagnosis of early mycosis

fungoides may be extremely difficult. In some instances, differentiation from

inflammatory skin conditions (e.g. psoriasis, chronic contact dermatitis) may

be impossible on histopathological grounds alone. In these cases, clinical

correlation is crucial to make a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistological

features are not distinctive, and are similar to those observed in many

inflammatory skin conditions. Staining for CD3 or CD4 may help by highlighting

epidermotropic T lymphocytes.4

Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome is characterized clinically by

pruritic erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy and the presence of

circulating malignant T lymphocytes (Sézary cells).4,5 Other typical

cutaneous changes include palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, alopecia and

onychodystrophy. Differentiation from non-neoplastic erythroderma may be

extremely difficult. The main causes of erythroderma, besides cutaneous T-cell

lymphoma, are atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and drug reactions. Erythrodermic

mycosis fungoides should be distinguished from true Sézary syndrome.

The presence of a monoclonal population of T

lymphocytes within the peripheral blood has been recently proposed by the

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous

Lymphoma Study Group, by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and

by others as an important criterion for the diagnosis of Sézary syndrome. Other

useful criteria include the presence of more than 1000 circulating Sézary cells/mm;

an expanded CD4+ population in the peripheral blood resulting in a markedly

increased CD4+ : CD8+ ratio (> 10); an increased population of CD4+ : CD7–

cells in the peripheral blood; Sézary cells larger than 14 μm in diameter; and

Sézary cells representing more than 20% of circulating lymphocytes.

Patients usually present with an abrupt onset of

erythroderma, or with erythroderma preceded by itching and a nonspecific skin

rash. Rarely, a classic Sézary syndrome may develop in patients with preceding

mycosis fungoides; it has been suggested to classify these cases as ‘Sézary

syndrome preceded by mycosis fungoides’, as it remains unclear whether the

clinical features and prognosis are similar. The presence of neoplastic T cells

within the peripheral blood alone should not prompt a diagnosis of Sézary

syndrome unless all other main diagnostic criteria are met.

The TNM staging classification used for mycosis

fungoides has also been adopted for Sézary syndrome. According to this system,

Sézary syndrome is classified as stage III by definition.4

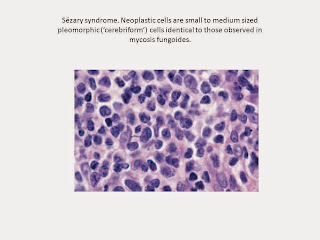

The histopathological features of skin lesions in

Sézary syndrome are indistinguishable from those of mycosis fungoides. Often

there is a psoriasiform spongiotic pattern with a variably dense band-like

infiltrate of lymphocytes. Epidermotropism is usually less marked than in mycosis

fungoides, but typical Darier’s nests ‘Pautrier’s collections’ may be observed.

Cytomorphology reveals a predominance of small to medium-sized pleomorphic

(cerebriform) lymphocytes, often referred to as ‘Sézary cells’. Differential

diagnosis from mycosis fungoides can be achieved only by correlation of

histopathological features with clinical ones. Histopathological variants of

Sézary syndrome include the presence of a prominent granulomatous reaction,

deposition of mucin within hair follicles (follicular mucinosis), or large cell

transformation. Large cell transformation may be detected in skin lesions,

lymph nodes, or both, and is indistinguishable from that occurring in advanced

mycosis fungoides. The lymph nodes are characterized by monomorphous

infiltrates of neoplastic cells, and reveal histopathological differences from

lymph nodes involved by cells of mycosis fungoides, suggesting a pathogenetic

difference between the two disease.4

Prognosis

Most cases of primary CTCL are not curable. Independent prognostic features in mycosis

fungoides include the cutaneous and lymph node stage of disease and age of onset (>60

years). The lymph node status and tumour burden within peripheral blood determine the

prognosis in Sezary syndrome. Serum lactate dehydrogenase and the thickness of the infiltrate in plaque-stage mycosis fungoides are also independent markers of prognosis. Multivariate analysis indicates that an initial complete response (CR) to various therapies is an independent favourable prognostic feature, particularly in early stages of disease. For mycosis fungoides, two staging systems are in regular use including a TNM (primary tumour, regional nodes, metastasis) system and a clinical staging specifically designed for CTCL. These staging systems can also be applied to Sezary syndrome, but neither system provides a quantitative method for assessing peripheral blood disease other than an additional B0 and B1 in the TNM system and this has prompted alternative approaches for Sezary syndrome. The 5- and 10-year overall survival (OS) in mycosis fungoides are 80% and 57%, respectively, with disease-specific survival (DSS) rates of 89% and 75% at 5 and 10 years respectively. Patients with very early stage disease (IA) are highly unlikely to die of their disease, with DSS rates of 100% and 97–98% at 5 and 10 years, respectively and risks of disease progression varying from 0% to 10% over 5–20 years.2,9

Treatment

Treatment for CTCL depends on the type and stage of

the disease. Treatment options include phototherapy, radiation, topical

therapy, systemic single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy and

combined therapies. Patients with localized early-stage disease are usually

treated with topical agents such as nitrogen mustard, skin-softening agents,

anti-itch agents and gradual exposure to sunlight or ultraviolet light.

Specific treatments include:

- Topical

nitrogen mustard

Nitrogen mustard or

Mustargen® is a chemotherapeutic agent that is administered as an ointment, an

aqueous solution or a liquid gel formulation. It is applied daily either to

affected areas of skin or to all skin surfaces. People in the early stage of

the disease respond best, but relapses are common after therapy is stopped.

- Photochemotherapy

Psoralen is a drug that

binds to the DNA in malignant cells. Patients take the drug by mouth and then

are exposed to ultraviolet light to activate the drug, which damages the

malignant cell DNA. This treatment often is referred to as PUVA, an acronym for

Psoralen and Ultraviolet-A light. Treatment is usually given several times a

week for one or two months, and less frequently thereafter. Maintenance treatment

is usually continued for a year or more. Patients in the early phase of disease

have the best response to treatment. Low-dose alpha-interferon, combined with

PUVA therapy, has shown promising preliminary results for patients with

early-stage disease. Narrow-band UVB, a form of phototherapy, is also used to

treat patch-stage cutaneous lymphoma.1,9,10

- Electron

beam radiation

Conventional radiation

therapy penetrates the skin and reaches areas inside the body. Electron beam

therapy can be applied to the entire skin surface without affecting internal

organs. This type of radiation has been helpful for patients who have skin

tumors. The tumors often heal after treatment and the dead tissue resolves,

reducing the risk of infection. Treatment leads to complete clearing of lesions

in several months without further treatment. Some patients appear to have

longstanding regression of their skin lesions following this type of treatment.

- Chemotherapy

Several combinations of

chemotherapeutic agents have been used in patients with skin lymphoma,

especially those with disease that involves the lymph nodes or other organs, or

those with Sézary syndrome. Effective therapies include methotrexate,

gemcitabine and liposomal anthracyclines. Other agents such as etoposide

(VP-16), cyclophosphamide and pentostatin may also be used. The most commonly

used drug combinations include cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and

prednisone.This particular drug combination may also be used for those patients

experiencing disease transformation or organ involvement. Chemotherapy has not

been able to cure widespread skin lymphoma, and studies using chemotherapy

combined with radiation therapy in patients with early stages of disease have

not been very successful.

- Other

drug therapies

Skin lymphomas are covered

under the U.S. Orphan Drug Act (1983). The Orphan Drug Act provides incentives

to induce sponsors to develop and manufacture drugs that otherwise might not be

profitable because of their small potential market. Since 1983, more than 200

drugs and biological products for rare diseases have been brought to market,

compared with 10 such products in the decade prior to 1983.

- Photopheresis

This procedure, also

called ECP for “extracorporeal phototherapy,” is a form of chemotherapy that

requires removal of blood through a vein and isolation of the white cells,

which includes circulating CTCL cells. The removed cells are treated with a

drug, 8-methoxsalen (UVADEX®), which sensitizes the cells to ultraviolet light.

An external source of ultraviolet A (UVA) rays is used to irradiate the cells,

which are then returned to the patient

through a vein. The ultraviolet light acting on 8-methoxsalen damages DNA of

the CTCL cells. The procedure must be repeated multiple times to gain the full

effect. It is believed that the effect is more extensive than killing removed

CTCL cells. It has been postulated that it involves a reaction of normal immune

cells against the UV light-damaged lymphoma cells. Thus, there may also be an

immune component because more CTCL cells are destroyed than the number

irradiated in the procedures. Photopheresis is most often used for advanced

stages of CTCL with signs of circulating CTCL cells in the blood. It is often

combined with other therapies. Photopheresis is also being studied in clinical

trials for early-stage disease.

- Supportive

therapy

The itching that accompanies

the skin lesions can be difficult to control. Antihistamines, particularly

Benadryl® or Atarax®, may relieve itching to someextent. However, the major

side effect of these drugs is drowsiness. Also, patients may develop a

resistance (tolerance) to the effectiveness of the drugs and require larger

doses. Application of skin softeners or steroid ointments may also help relieve

itching. Antibiotics are given if lesions become infected. Patients with

long-standing, troublesome symptoms may require treatment for depression or

insomnia.1,7,9,11,12

References

1. cutaneus T Cell Lymphoma. Available at: www.leukemia-lymphoma.org/attachments/.../br_1163608564.pdf.

2.

Williams H. Bigby M. Diepgen T. Herxheimer A. Naldi L.

Rzany B. Evidence Based Dermatology: Primary Cutaneus T cell Lymphoma. BMJ.

London. 2003 : 344-345.

3.

Twenty-Year Trends in the Reported Incidence

of Mycosis Fungoides and Associated Mortality. Available at: www.ajph.org/cgi/content/abstract/89/8/1240.

4.

Cerroni

L. Gatter K. Kerl H. An Illustrated Guide to Skin Lymphoma: Cutaneus T Cell

Lymphoma. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. USA

5.

Kumar V, Abbas A.K, Fausto N. Pathologic Basis of

Disease: Mycosis Fungoides. Elsevier Saunders. Philadelphia . 2005: 685.

6.

Raphael R. Strayer D.S. Rubin’s Pathology:

Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Philadephia. 2008: 921.

7.

Pillsbury D.M. Shelley W.B. Kligman A.M. Dermatology:

The Lymphoma. W.B.Saunders Company. Philadelphia .

1960: 1089-1093.

8.

Girardi M. Heald P.W. Wilson L.D. The Pathogenesis of

Mycosis Fungoides. NEJM. Volume 350: 1978-1988.

9.

Suarez Varela M.M.M. Cutaneus T Cell Lymphoma. CRC

Press. 2005: 1-32.

10.

The Addition of Interferon

Gamma to Oral Bexarotene Therapy With

Photopheresis for Sézary Syndrome. Available at: http://archderm.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/extract/141/9/1176.

11.

Bickers D. Henry W.Lim.

Margolis D. Weinstock M. The Burden of Skin Disease. The Lewin Group Ltd. Washington . 2004: 29-31.

12.

Classification

and Treatment of Rare and Aggressive Types of

Peripheral T-Cell/Natural Killer-Cell

Lymphomas of the Skin. Available at: www.moffitt.org/moffittapps/ccj/v14n2/pdf/112.pdf.

I'm 55-year-old from Paris, I was diagnosed with second-stage liver cancer following a scheduled examination to monitor liver cirrhosis. I had lost a lot of weight. A CT scan revealed three tumors; one in the center of my liver in damaged tissue and two in healthy portions of my liver. No chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment was prescribed due to my age, the number of liver tumors. One month following my diagnosis I began taking 12 (350 point) Salvestrol supplements per day, commensurate with my body weight. This comprised six Salvestrol Shield (350 point) capsules and six Salvestrol Gold (350 point) capsules, spread through the day by taking two of each capsule after each main meal. This level of Salvestrol supplementation (4,000 points per day) was maintained for four months. In addition, I began a program of breathing exercises, chi exercises, meditation, stretching and stress avoidance. Due to the variety of conditions that I suffered from, I received ongoing medical examinations. Eleven months after commencing Salvestrol supplementation But all invalid so I keep searching for a herbal cure online that how I came across a testimony appreciating Dr Itua on how he cured her HIV/Herpes, I contacted him through email he listed above, Dr Itua sent me his herbal medicine for cancer to drink for two weeks to cure I paid him for the delivering then I received my herbal medicine and drank it for two weeks and I was cured until now I'm all clear of cancer, I will advise you to contact Dr Itua Herbal Center On Email...drituaherbalcenter@gmail.com. WhatsApps Number...+2348149277967. If you are suffering from Diseases listed below,

BalasHapusCancer

HIV/Aids

Herpes Virus

Bladder cancer

Brain cancer

Colon-Rectal Cancer

Breast Cancer

Prostate Cancer

Esophageal cancer

Gallbladder cancer

Gestational trophoblastic disease

Head and neck cancer

Hodgkin lymphoma

Intestinal cancer

Kidney cancer

Leukemia

Liver cancer

Lung cancer

Melanoma

Mesothelioma

Multiple myeloma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Oral cancer

Ovarian cancer

Sinus cancer

Skin cancer

Soft tissue sarcoma

Spinal cancer

Stomach cancer

Testicular cancer

Throat cancer

Thyroid Cancer

Uterine cancer

Vaginal cancer

Vulvar cancer

Hepatitis

Chronic Illness

Lupus

Diabetes

Fibromyalgia.