Gastric cancer

is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause

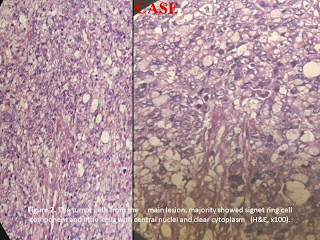

of cancer related death worldwide. Signet-ring cell cancer is a subtype of

adenocarcinoma, which is the most common type of cancer arising from the

stomach. It has a distinct appearance under the microscope as a result of the

clear mucin it produces either inside or outside the cells. The natural course

of patients with signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach remains poorly

understood while assumptions have been made to distinguish it from other types

of gastric cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer

is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause

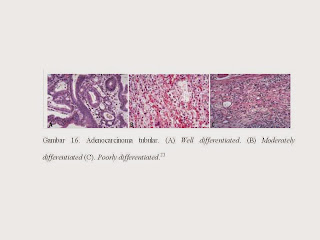

of cancer related death worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of

cancer arising from the stomach. The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the stomach

is declining worldwide. Today, gastric cancer is still the seventh most common

cause of cancer-related death in the United States and the prognosis of

advanced gastric cancer remains poor. Signet-ring cell cancer is a subtype of

adenocarcinoma, which is the most common type of cancer arising from the

stomach. The natural course of patients with signet ring cell carcinoma of the

stomach remains poorly understood while assumptions have been made to

distinguish it from other types of gastric cancer. 1-10 It has a distinct appearance under the

microscope as a result of the clear mucin it produces either inside or outside

the cells. In most series, this cancer

has a poor prognosis.8 Signet ring cell carcinoma is a descriptive

term used to denote a form of mucin-secreting adenocarcioma whose component

cells retain abundant intracytoplasmic mucin, pushing their nuclei to one side,

creating

a classical signet ring cell appearance thereby giving the cells their characteristic histological appearance.1-6,8

Signet

ring cell carcinoma is poorly cohesive carcinomas and often composed of a

mixture of signet ring cells and non-signet ring cells. Those tumor cells can

form irregular microtrebaculae or lace-like abortive glands, often accompanied

by marked desmoplasia in the gastric wall and with a grossly depressed or

ulcerated surface.1,2,3-9 The overall survival rate of patients

with signet ring cell carcinoma was worse than that of patients with other

types of gastric cancer.1,4

Gastric cancer is the fourth most commonly

diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer related death

worldwide. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has gradually decreased

over the last half century, cancer at proximal stomach is on the rise. Today,

gastric cancer is still the seventh most common cause of cancer-related death

in the United States and the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer remains poor.

Gastric carcinogenesis is a multistep and multifactorial process.1,10

Histologically, gastric carcinoma demonstrates marked heterogeneity at both

architectural and cytologic level, often with co-existence of several

histologic elements. Gastric cancer incidence rates for men are approximately

twice those of women in all populations for persons over 50 years of age, but

the male:female incidence ratio is 1 or less at younger ages. The age-related

variation in the male:female incidence ratio suggests that host factors may

influence the level of risk of acquiring this cancer.2,3

Gastric carcinoma is clinically classified as

early or advanced stage to help determine appropriate intervention, and

histologically into subtypes based on major morphologic component. Early

gastric carcinoma is defined as invasive carcinoma confined to mucosa and or

submucosa, with or without lymph node metastases, irrespective of the tumor

size. Most early gastric carcinomas are small, measuring 2 to 5 cm in size, and

often located at lesser curvature around angularis. Some early gastric

carcinoma can be multifocal, often indicative of a worse prognosis.1,10

Advances gastric

carcinoma which invades into muscularis propria or beyond carries a much worse

prognosis, with a 5 years survival rate at about 60% or less.10 In this case, the tumor cells have been

extension to the muscularis propria, and surgical margins still found tumor

cells. The gross appearance of advanced gastric

carcinomas can be exophytic, ulcerated, infiltrative or combined. Based on Borrmann’s

classification, the gross appearance of advanced gastric carcinomas can be

divided into type I for polypoid growth, type II for fungating growth, type III

for ulcerating growth, and type IV for diffusely infiltrating growth which is

also referred to as linitis plastica in signet ring cell carcinoma when most of

gastric wall is involved by infiltrating tumor cells. 3,4,7,10 Histologically, advanced gastric

carcinoma often demonstrates marked architectural and cytological

heterogeneity, with several co-existing histologic growth patterns. The

distinction between early and advanced gastric carcinoma before resection is

clinically important because it helps decide if a neoadjuvant (pre-operative)

therapy which has shown to improve disease free survival and overall

survival is warranted. While the

macroscopic appearance is informative, the most accurate pre-operative staging

information is generally obtained with endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and

computer tomography (CT).7,10

Over the past

half century the histologic classification of gastric carcinoma has been

largely based on Lauren’s criteria (intestinal type and diffuse type), in

dominant elements of other histologic patterns.1-10 While the

intestinal type of gastric cancer is often related to environmental factors

such as Helicobacter pylori infection, diet, and life style. The diffuse type

is more often associated with genetic abnormalities. The intestinal type of gastric cancer is thought to arise from the

metaplastic epithelium (Lauren 1965), whereas signet ring cell carcinoma in the

diffuse type is thought to arise from the mucosa that is not metaplastic and is

confined to the glandular neck region in a proliferating zone (Carneiro et al,

1992; Kitamura et al. 1996).4 Signet-ring cell carcinomas are

infiltrative; the number of malignant cells is comparatively small and

desmoplasia may be prominent. Signet ring carcinomas are tumors in

which >50% of the mass consists of isolated or small groups of malignant cells containing

intracytoplasmic mucin that compresses the nucleus to the periphery of the

cell membranes. The classic signet ring cells are most numerous in the

superficial portions of the tumor where they are stacked in a layered fashion. Superficially, cells lie scattered in

the lamina propria, widening the distances between the pits and glands. The tumour cells have five morphologies: (1)

Nuclei push against cell membranes creating a classical signet ring cell

appearance due to an expanded, globoid, optically clear cytoplasm. These

contain acid mucin and stain with Alcian blue at pH 2.5; (2) other diffuse carcinomas

contain cells with central nuclei resembling histiocytes, and show little or no

mitotic activity; (3) small, deeply eosinophilic cells with prominent, but

minute, cytoplasmic granules containing neutral mucin; (4) small cells with

little or no mucin, and (5) anaplastic cells with little or no mucin. These

cell types intermingle with one another and constitute varying tumour

proportions. Signet-ring cell tumours may also form lacy or delicate trabecular

glandular patterns and they may display a zonal or solid arrangement.1-6

Signet ring

cancers usually exhibit the infiltrating growth pattern and desmoplasia that is

called diffuse cancer in the Lauren classification. Infiltrating Borrmann type

IV carcinomas are usually signet ring tumors. The tumor cells in the deeper

portions of the stomach wall have less cytoplasmic mucin and more centralized

nuclei. They may be so widely dispersed through the stroma that they may be

difficult to detect in routine H&E - stained preparations. Some form of

mucin stain (periodic acid Schiff, Alcian blue, mucicarmine) or

immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin antibodies may be used to detect

these cells.1-6 Special stains, including mucin stains (PAS, mucicarmine, or

Alcian blue) or immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to cytokeratin,

help detect sparsely dispersed tumour cells in the stroma. Cytokeratin

immunostains detect a greater percentage of neoplastic cells than do mucin

stains. Several conditions mimic signet-ring cell carcinoma including signet-ring

lymphoma, lamina propria muciphages, xanthomas and detached or dying cells

associated with gastritis.1,2

The clinicopathological characteristics of signet ring cell

carcinoma of the stomach are known to differ from that of other types of

gastric cancer. Some have reported a higher rate of forming multiple gastric

cancers if the primary lesion is signet ring cell carcinoma. Early gastric

cancer with signet ring cell histology tends to be superficial and large,

leading to earlier diagnosis than gastic cancer of other histological types.

The superficial spreading nature may be helpful for early detection, because it

has less chance of being missed during endoscopy.7,10

In addition to a superficial spreading nature, the formation

of satelite lesions may be a significant characteristic of signet ring cell

carcinoma. Despite the advancement in diagnostic tools, a proportion of gastric

cancers often remain undetected. Some reports assert that early signet ring

cell carcinoma of the stomach tends to spread in the mucosal and submucosal

layers continously or discontinously. This may explain the prevalence of

multiple gastric cancers in the signet ring cell carcinoma. As an early gastric

cancer, signet ring cell carcinoma is known to have a tendency to form multiple

lesions. However, once the disease evolves into advanced gastric cancer, the

diffusely infiltrating characteristics of signet ring cell carcinoma may be

associated with a poor prognosis by involving the entire stomach, resulting in

what is known as linitis plastica. Advancement in diagnostic tools along with

signet ring cell carcinomas tendency to spread superficially may have resulted

in an apparently slow progression of this cancer. Although the results are not

consistent, some reports discuss that, as an early gastric cancer, signet ring

cell carcinoma has a favorable prognosis with less lymph node metastasis.7,8

When it occurs at the antropyloric region with

serosal involvement, the carcinoma tends to have lymphovascular invasion and

lymph node metastasis. Because signet ring cell and other poorly cohesive

carcinomas at antroplyoric region have a propensity to invade duodenum via

submucosal and subserosal routes including subserosal and submucosal lymphatic

spaces, special attention needs to be paid to those routes when a distal margin

frozen section is requested at the time of surgical resection. In this case,

tumor locate is unknown but the tumor cells have been infiltrated the

muscularis serosa. One important differential diagnosis of neoplastic signet ring

cells in gastric mucosa is benign pseudo-signet ring cells which can remarkably

mimic signet ring cell carcinoma. Those pseudo-signet ring cells sometimes can

demonstrate cytological atypia, even with mitoses. However, those pseudo-signet

ring cells do not reveal invasive pattern with reticulin stain which highlights

pseudo-signet ring cells confined within basement membrane with intact acinar

architecture.1,2,3,-9

There

were demographic differences between the two tumor types as well. In patients

with intestinal-type carcinoma, 65% were men and the average age was 55.4

years; in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma, 54% were men and the average age was

47.7 years. Approximately 60% of gastric cancers in high-risk

populations, are most common in the antrum. 1,2,4-6 The reasons for

age variation remain unknown; possibilities include genetic heterogeneity

between different CDH-1 mutations, other gene-gene interactions, or

environmental factors.7 The diffuse phenotype in gastric cancer

(hereditary and sporadic) is related to reduced E- adherin expression. It has

been suggested that loss of E-cadherin is the fundamental defect in diffuse

type gastric carcinoma, and provides an explanation for the observed

morphological phenotype: discohesive cells with loss of polarity and gland

architecture. In contrast, gland architecture is preserved in the intestinal

type of stomach cancer where loss of E-cadherin expression is not a feature.7

Diffuse carcinomas consist of

discohesive cells that penetrate through the stomach wall as individual cells

embedded in a desmoplastic stroma. As compared to the cells in intestinal-type carcinomas,

diffuse carcinoma cells were smaller, more uniform in overall shape and in

nuclear size, and had less mitotic activity. Epithelial structures formed by these

cells were more abortive, with only rare lumen formation. To the naked eye,

diffuse carcinomas did not form well-defined masses in many cases, and

microscopically showed extensive infiltration of the mucosa without associated

ulceration. Thirtyone per cent of these tumors were described as polypoid or

fungating; 43% were described as having a linitis plastica growth pattern. They appear

as layered signet ring cells in the superficial portions of the mucosa, but

signet ring cells are less numerous in the deeper portions of the wall, where

more pleomorphic cells predominate. Cell cycle markers may fail to label

superficial signet ring calls, in contrast to the discohesive cells that

infiltrate deeper into the gastric wall. A few inconspicuous, abortive glands

may be present. The desmoplastic reaction that accompanies diffuse cancer may

be more conspicuous than the cancer cells that elicit it.1,2,5

Molecular pathology in gastric carcinoma. An accumulation of genetic and molecular abnormalities occurs during gastric carcinogenesis, including activation of oncogenes, overexpression of growth factors/receptors, inactivation of tumor suppression genes, DNA repair genes and cell adhesion molecules, loss of heterogeneity and point mutations of tumor suppressor genes, and silencing of tumor suppressors by CpG island methylation and alterations in cell cycle regulatory genes. Inherited factors interact with environmental hazards to increase gastric cancer risk in two ways: (a) germline mutations account for well-defined, but infrequent, familial cancer syndromes; and (b) polymorphisms in genes that govern cell cycling or enzymes that catalyze carcinogen detoxification may also influence gastric cancer risk. Other types of changes occur in sporadic tumors.2,10Inherited gastric cancer predisposition syndromes account for approximately 10% of gastric cancers. The genetic events are known for some but not all of the predispositions. The hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNPCC) is an example of the interaction of environmental hazards with germline mutations. Persons with this autosomal dominant condition are at increased risk of developing cancer at sites other than the colon, including the stomach. HNPCC is due to a germline mutation in mismatch repair genes.1-3,5,10 There is some molecular overlap between the two types of gastric carcinoma; for example, mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53 are seen in both types of gastric carcinoma, as is silencing (by hypermethylation) of the mismatch repair gene MGMT. Defects in the CDH1 gene are almost exclusive to diffuse-type carcinomas. The CDH1 gene codes for the e-cadherin protein, which is important in cell–cell adhesion. Loss of expression of this protein correlates with loss of cohesion, leading to tumors that diffusely infiltrate as single or small groups of cells, often with intracellular accumulation of mucin giving a signet-ring appearance to the individual cells. This phenotype is mirrored by infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast. Most gastric carcinomas occur sporadically; only About 10% of gastric carcinomas show familial clustering but only approximately 1-3% of gastric carcinomas arise from inherited gastric cancer predisposition syndromes, such as hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma (HDGC), familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (or Lynch syndrome), juvenile polyposis syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome and gastric hyperplastic polyposis. HDGC is an autosomal dominant disorder with high penetrance. Approximately 30% of individuals with HDGC have a germline mutation in the tumor suppressor gene E-cadherin or CDH1. The inactivation of the second allele of E-cadherin through mutation, methylation, and loss of heterozygosity eventually triggers the development of gastric cancer. In the familial syndrome hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma (HDGC), diffuse gastric carcinoma and occasionally infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast develop in young adults. Germline mutations in the CDH-1/E-cadherin gene are, to date, the only known cause of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). E-cadherin is a member of the cadherin family of homophilic cell adhesion proteins that are central to the processes of development, cell differentiation, and maintenance of epithelial architecture. It is the predominant cadherin family member expressed in epithelial tissue and is localised at the adherens junctions on the basolateral surface of the cell. E-cadherin is downregulated in a broad range of epithelial tumours and its loss is associated with an infiltrating phenotype and poor prognosis.1,3,5,7,10 Recently, E-cadherin gene (CDH1) germ-line mutations have also been identified as the underlying genetic basis for another familial gastric cancer syndrome that is characterized by early occurrence of diffuse type adenocarcinoma. These patients are also at risk for developing lobular breast cancer. Sporadic gastric carcinomas, especially diffuse carcinomas, exhibit reduced or abnormal E-cadherin expression, and genetic abnormalities of the E-cadherin gene and its transcripts. Reduced E-cadherin expression is associated with reduced survival. Somatic E-cadherin gene alterations also affect the diffuse component of mixed tumours. Alpha-catenin, which binds to the intracellular domain of E-cadherin and links it to actin-based cytoskeletal elements, shows reduced immunohistochemical expression in many tumours and correlates with infiltrative growth and poor differentiation. Beta catenin may also be abnormal in gastric carcinoma. 1,2,5,6,7,10 Clinical features, gastric cancers that elicit symptoms are usually late-stage tumors and are more likely to precede the diagnosis of cancer in Western, unscreened populations than in Asia or other high-risk areas. The early cancers that may accompany chronic gastric ulcers are exceptions to this rule. A review of 18,265 stomach cancers by the American College of Surgeons found the following frequently overlapping symptoms to be the most common: Weight loss (61.6%), abdominal pain (51.6%), nausea (34.3%), dysphagia (26.1%), and melena (20.2%). Weight loss is an ominous presenting symptom and associates with poor survival. Early satiety may result from either pyloric obstruction or the ability of the stomach to expand. Blood loss from an ulcerated tumor may induce anemia and fatigue. Infection of necrotic, fungating tumors may cause fever. Spread of gastric cancer to a distant site is the presenting symptom in some cases. This may take the form of an enlarged supraclavicular lymph node. Ascites or vaginal bleeding due to endometrial metastases may be the presenting symptom in premenopausal women with diffuse cancer.1,2Lymphatic spread occurs early, and as noted above, may even be observed with small submucosal cancers. Lymphatic and vascular invasion carries a poor prognosis and is frequently seen in advanced cases. Surgical resection margins should be monitored by frozen section because gross assessment is inaccurate and margin involvement occurs in 15% of cases. The pathologist should take pains to identify the proximity of the cancer to the radial margin, which is defined as the surgically dissected surface adjacent to the deepest point of tumor invasion. A deeply penetrating cancer that centers on the lesser or greater curvature may have a radial margin that lies in the connective tissue of the lesser or greater omentum, rather than the serosal surface. Microscopic involvement of a resection margin is almost synonymous with early recurrence or death.2Treatment, surgical removal of stomach cancer is the treatment of choice, although, if you say the cancer has spread, an operation to remove the cancer is unlikely to be of benefit. Several clinical studies have reported results that indicate a moderate survival or palliative benefit for patients with advanced stomach cancer. There is no combination of chemotherapy which is clearly superior to others, but most active regimens include 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Cisplatin, and/or Etoposide. The combination of 5-Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin (FAM) has been used in the past with modest success. There was no statistically significant difference in survival among the various chemotherapy combinations on their preliminary report.9 The almost limitless heterogeneity of most advanced gastric cancers creates a barrier to the development of customized chemotherapeutic approaches. Palliation, rather than cure, is the primary goal of adjuvant therapy. Most patients who have had a resection for gastric cancer with extensive lymph node metastases will have a disease relapse. No randomized trial has shown a benefit for this subset of patients and no single agent has proved effective for postoperative chemotherapy. This is not unexpected since successful response to treatment with drugs that target specific oncogenes allows subsets of other cells to survive and serve as the seedbeds for recurrent tumors. 2,4 As far as diet, nitritional support of stomach cancer is a very important component of the treatment. Many patients are malnourished with some extent of weight loss prior to their diagnosis. If he is able to eat, well balanced diet with adequate protein and vegetables is appropriate.9Prognosis and predictive factors, when early gastric cancer is confined to the mucosa or is node negative, the reported five year survival is now over 90% in almost all Western and Japanese series.7 Lymphatic and vascular invasion carries a poor prognosis and is often seen in advanced cases and it is also an important prognostic indicator. Patients who had nodal involvement in 1-6 lymph nodes (pN1), the 5-year survival rate was 44% compared with a 30% survival rate in patients with 7-15 lymph nodes involved with tumour (pN2). Patients with more than 15 lymph nodes involved by metastatic tumour (pN3) had an even worse 5-year survival of 11%. Gastric carcinoma with obvious invasion beyond the pyloric ring, those with invasion up to the pyloric ring, and those without evidence of duodenal invasion have 5-year survival rates of 8%, 22%, and 58%, respectively.m. Patients with T1 cancers limited to the mucosa and submucosa have a 5-year survival of approximately 95%. Tumours that invade the muscularis propria have a 60-80% 5-year survival, whereas tumours invading the subserosa have a 50% 5-year survival. Unfortunately, most patients with advanced carcinoma already have lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis.1,5Histological features. The value of the histological type of tumour in predicting tumour prognosis is more controversial. The overall survival rate of patients with signet ring cell carcinoma was worse than that of patients with other types of gastric cancer. The late stage of signet ring cell carcina could not axplain this difference. Because of the frequency of peritoneal dissemination, strong consideration should be given to evaluating the role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The recent study also revealed that early signet ring cell carconama of the stomach is not lethal as was previously beleived (Tso et al. 1987).1,4Cytologic subtyping of gastric cancer is not essential. If one equates papillary, tubular, and some mucinous carcinomas with Lauren's intestinal-type and signet ring cell carcinoma with the diffuse type, then a specificity rate for cytologic typing of >90% for the former and of 85% for the latter may be obtained. However, vacuolized cells should be evaluated with special care because signet ring cells are easily simulated by goblet cells. The size of the nucleolus and the nuclear outline are helpful differential diagnostic features. Unless fine needle aspiration is combined with the endoscopic examination, early gastric carcinoma cannot be identified cytologically because no features exist that allow one to distinguish between early and advanced gastric cancer. 2Machara et al, 1992 reported that patients with signet ring cell carcinoma can expect a longer survival than those with other types of gastric cancer. In contrast, Kim et al, 1994 reported that there was no significant difference in the 5-year survival rates between patients with early signet ring cell type and those with other types of advanced cancer. Multivariate analysis showed the significant prognostic factors to be vascular invasion and tumor location. Microinvasion has been reported tobe a major independent risk factor for long-term survival (Yokota et al. 1998). Microinvasion may represent an early finding of metastatic spread of gastrointestinal tumors, and capillary microinvasion could predispose to distant metastasis. The tumor location was also an important prognostic variable, and cancer that had invaded the whole stomach was worse than that for patients with cancer that had invaded only the antrum and body of the stomach. 4

References

1. Hamilton S R, Aaltonen L A. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System.Tumours of the Stomach. IARC Press. Lyon, 2000. p.35-50.

2. Preiser F. Cecilia M, Noffsinger, Amy E. The Neoplastic Stomach. In: Gastrointestinal Pathology: An Atlas and Text, 3rd Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008.p.234-70

3. Henson DE, Dittus C, Younes M, et al: Differential trends in the intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in the United States, Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:765.

4. Yokota T, Kunii Y, Teshima S, et al. Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma of the Stomach: A Clinicopathological Comparison with the Other Histological Types. Available from: www.journal.med.tohoku.ac.jp.pdf. 20/1/2014. 01.30

5. Hall C R. Pathology of Gastric cancer. In: Gore R M. Reznec R H. Gastric Cancer. Contemporary Issues in Cancer Imaging. A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge University Press. 2010.p.22-42.

6. Lin C, Crawford J M. The Gastrointestinal Tract. In: Kumar V, Abbas A K, Fausto N. Robbin and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh Edition. Elsevier Saunders. 2005.p.871-.

7. Lee S S, Ryu S W, Kim I H et al. Early Gastric Cancer with Signet Ring cell Histology Remained Unresected for 53 Moths. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc. on February 21, 2014. 15:37.

8. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: predominance of multiple foci of signet ring cell carcinoma in distal stomach and transitional zone. Available from: gut.bmj.com . On February 20, 2014. 14:52.

9. Liu L. Signet Ring Cell Cancer. Available from: www.oncolink.org. On February 2, 2014. 04:26.

10. Hu B, Hajj N E, Sittler S et al. Gastric cancer: Classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. Available from: http://www.thejgo.org/article/view/427/html On February 2, 2014. 04:05.